POSTSCRIPT: COUNTACH’S SAD FAREWELL…

High up on London’s A40 Westway, just where it climbs away from Marylebone Road and heads west over the rooftops for Oxford, a metallic gold Lamborghini Countach was being smashed to pieces.

Some fool had chopped across its path mid-bend. It started spinning in great big arcs, thumping into the barrier on one side of the road and being flung back to smash against the other side.

The nose was pounded back to the windscreen in the first gyration, taking the front wheels with it. The side had already gone and, as it slammed into the barrier for the last time, the tail was flattened to the engine – that glorious V12.

I was driving the other way, into London, and saw it happening right there in front of me. I couldn’t believe it. I shouted with anguish…horror…anger. Even in the blur of the destruction, before it had stopped and I had parked to run across and see if the driver was all right, I knew it was my Countach.

We’d only had 48 hours together. But each hour, every single minute, was a jewel that I, and the three others who’d shared the experience, will treasure forever. That Countach, along with the Silhouette and Urraco, was the one that had whisked us halfway across Europe in our epic high-speed convoy.

Its occupants were able to swing the doors up and step out, shaken but uninjured. The windscreen hadn’t broken, even though the nose had been so hideously flattened and the severity of the impact, I’d learn later, had cracked the alloy of the crankcase and transmission. In death, as in life, that car was magnificent.

Before I continue, I’ll stress now that this is very high-level, unscientific, subjective post full of assumptions on my behalf, and covering only a fraction of all the available chassis designs out there! So caveating done, and fully open to correction and addition…….

What ever about old cars crash worthiness (and watching a Sierra doing an offset impact @ 40 is depressing viewing) I often wonder about supercars & their viability in a thump. Body engineering in the 60s, where CAR magazine coined the popular use of the word ‘supercar’, could be fairly rudimentary. Here’s an original GT40 being crash-tested into a fixed barrier @ 41mph in 1967.

The purpose of the test was to see what the addition of the rollcage did to driver safety. The spray was ‘Staddard Solvent’ in the fuel tank. This approximated the weight of fuel closest, but had a very high flashpoint. The front wheels crushed the tanks, causing fuel to be ejected, and the crushed bodywork caused that ejected fuel to be sprayed all over the car. Neat, eh? So things needed to move on quickly from here.

Sticking generally to the Lamborgini theme, here’s how their evolution went.

The 1966 Muira chassis:

The Chief Engineer for this car was Gian Paolo Dallara. The design of this chassis was proper ‘old-school’, full of Italian passion for the genre, and completed instinctively and swiftly - 7 months in total! It went from a bare rolling chassis in Nov-65 to having a complete car in Mar-66. 29 year old Dallara and his small, equally young & inexperienced team did the entire car.

The key people were Paulo Stanzani in charge of stress analysis, Achille Bevini chassis development, Bob Wallace chassis testing, Mr Pedrazzi engine development, Roberto Frignani engine testing, and Gianni Malosi for bringing the whole thing to production.

They used steel simply because the local expertise lay with crafting it and not aluminium. It was constructed from straight pieces with only simple bends if really necessary. This was due to the budget not stretching to tooling or dies, leading to simple fabrication. There were holes punched to save weight, which was the only stamping done.

Torsional rigidity was tested, but as they had nothing to reference it against, they didn’t pay too much attention. Ford bought an early example, presumably to benchmark with the GT40, and gave good feedback on rigidity and also did some testing that led to Dallara strengthening a transverse link that broke on Fords Belgian Pave track.

Low volume supercars seemed to migrate to tubular spaceframes soon after - they give great strength/rigidity-to-weight ratios, but their inherent strength and ability to carry high loads in an impact scenario isn’t great as it causes high occupant deceleration. And then the eventual mode of failure (i.e. instability through buckling) has the opposite issue as it offers the least energy absorption. So it was difficult back then to integrate an effective crumple zone into these.

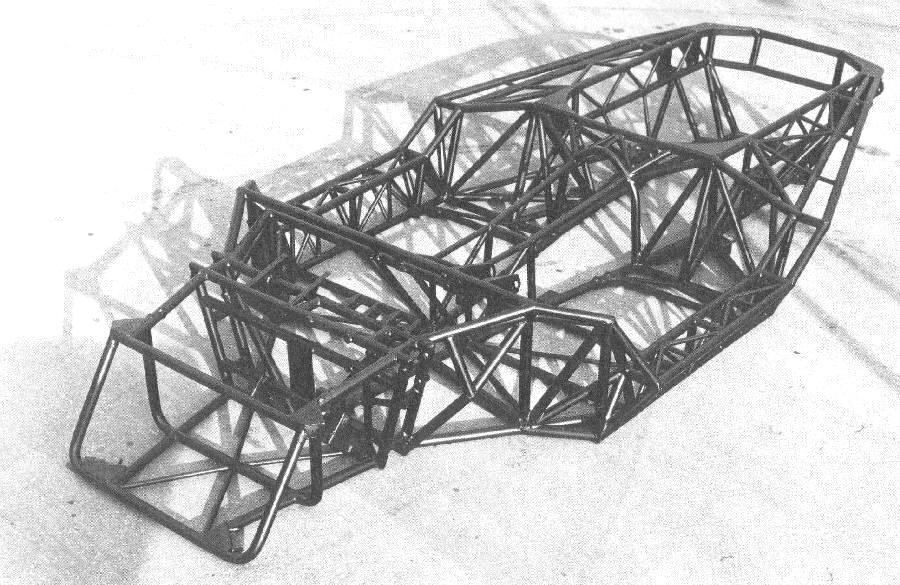

From the description of the robust protection the gold 1,100kg 395bhp Countach offered, I said I’d show a spaceframe Countach chassis.

Complex looking, isn’t it? And notable for a serious lack of structural roll-over protection! The addition of the upper structure doesn’t really improve things.

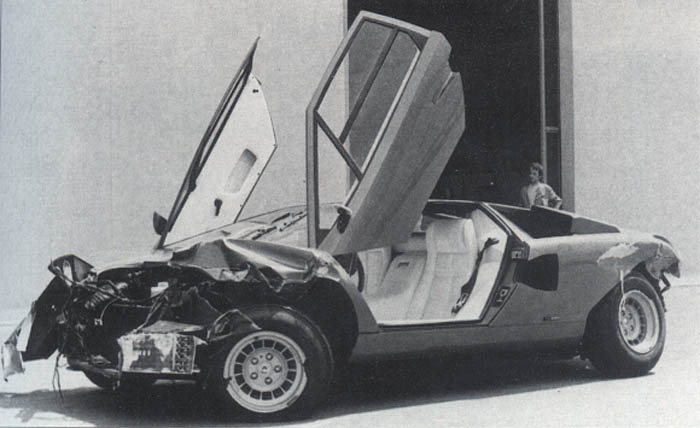

Never the less it is safe to assume that, in the context of cars back then, the spaceframe was a strong enough thing to be sat within in the event of a crash:

The Diablo was an evolution from the Countach spaceframe philosophy although the chassis itself was all new. Where the F40s of this world were applying some cutting edge technology with composites in the floorpan, bulkheads, and body panels the Diablo stayed predominantly old school (as admittedly did the Testarossa & it’s evolutions), except for near the end when the 6.0 started adding carbonfibre bodywork & selected composite structural reinforcement.

It’s hard to put any crash photo into context as you don’t know speed, point of impact etc etc. But this photo is of interest as I think it shows how an apparently minor impact can make the spaceframe chassis go from strong to unstable; you would imagine the A-pillar deflection might have be reduced if those spidery pillars were designed to take some decent loadings as on a monocoque.

.

.

It’s worth noting that the Diablo, and all supercars, often suffer because the point of impact is higher than its crash structure. Note below how the chassis almost folds up, and the wheels and floorpan show little evidence of direct impact deformation, it's all almost secondary to the impact higher up on bulkhead and A-pillars.

As an aside, another example of old-school, low-volume chassis design is a TVR Tuscan

In this instance it’s a bit of a hybrid between the backbone chassis (itself a Lotus invention for the Elan) & spaceframe chassis - the rigidity is provided by the central ‘backbone’ rather than via the sills like the Countach, but the backbone is made in a spaceframe lattice. But while this benefits entry & exit, it doesn’t do much for side impact.

Back to Lambo; with the introduction of the Murcielago, Lamborghini stayed old-school where (admittedly more expensive) F50s and MacLaren F1s moved to full carbon fibre tubs. The Murcielago still uses a tubular spaceframe at its core evolved from Countach & Diablo days, but increasing the strengthening with carbonfibre & honeycomb additions attached with a mix of steel rivets & adhesive. It has a structural steel roof, carbon fibre floorpan, rear arch steel tube replacement with carbon fibre panels, and some steel stiffening panels too. And most of its panels are carbonfibre too. Interestingly the 550 Maranello was also deemed to be a steel spaceframe with alloy panels welded to it, though in the shots I’ve seen it appears to be a monocoque.

There is an interesting back story to the Murcialagos creation - it was nearly a Zonda. Lamborghini were restyling the Diablo in 1997, and were unhappy with the results. Hearing about Paganis development work, they had a notion to take over his Zonda project, drop the existing V12 drivetrain into it, and make it a Diablo replacement. The visited Horacio, loved what they found, and offered $9m to take it over which was very attractive to Pagani as it had been all self-financed and he didn't have enough money at the time to complete the project. It was Paganis then 10yr old son Leonardo who said 'it's been your dream to build this car all your life, the dream is coming true, can you cope if you lose it?'. And the rest is history.... The Zonda launched in 1999, and Lamborghini re-skinned and evolved the Diablo to become the Murcialago.

The fresh-sheet Gallardo chassis used Audi experience and is an aluminium spaceframe. This sounds similar to a steel spaceframe, but to me looks more like a steel monocoque shape with the sheet metal sections cut out. Here's an (Audi) example to illustrate what I mean:

The Gallardo comprises of aluminium extrusions welded to cast joint elements, with it’s aluminium bodywork fixed on with rivets, screws, or welded depending on each bits functionality. I couldn’t find a decent photo of a Gallardo chassis, so here’s an Aston Martin instead which is conceptually the same.

Ferrari adopted an ally monocoque with tubular spaceframes front & rear for the F360, which is another variation on the theme.

And the new Aventador has an all-carbon chassis which is cutting edge and boast crash protection, and torsional stiffness a multiple of its forebears.

I’d love to see modern supercars EuroNCAP performances. I’d especially like their testing to simulate impacts into vehicles that have higher crash structures. Although, the resultant legislation might mean higher noses and gargantuan A-Pillars, so maybe it is best to sacrifice safety for aesthetics?

Anyway, hope I haven't bamboozled you all. It was a bit of a stream of conciousness supported by some internet digging so it mightn't be too cohesive!

No comments:

Post a Comment